By Mark Kingkade and Howard Penrose

Over the years, two groups of vibration analysts have been involved in the use of triaxial sensors. We want to express our thoughts on the subject from an end-user perspective. It has come up more now that many of our wireless vibration sensors on the market are triaxial, and they are not always installed in the best locations.

These two separate issues are causing a lot of discussion and distrust in technology and causing defects to go undetected. We will start with a focus on the triaxial versus single-axis sensors. We will also discuss the installation location.

Understanding the Triaxial Data Collection Process

Let us start with the triaxial data collection process. I (Mark) started doing multi-channel data collection around 2002. Then, it was all dual channel using two single-axis accelerometers mounted as close to the optimal location as possible.

The primary reason was to help reduce the time spent collecting the raw data in the field. The vertical and horizontal data on each bearing were collected at the same time. When possible, I would pair the axial data points with each other to take data across the coupling.

Using triaxial sensors cut my data collection time in the field by about half.

Doing this cut my route data collection by over 1/3 since it was dual channel. In 2016, I got my first triaxial sensor and began using it, which cut my data collection time in the field by about half. This is when a lot of the application discussions started for me. The main reason so many people opposed it was that at least one radial axis would not be aligned with the center line of the shafts.

Then, the axial data would also be further away from the shaft, which would have a detrimental effect on the data, especially the amplitude levels. However, if you think about the axial data, you will not be able to get close to the shaft unless you have a side exit accelerometer.

All are valid points, but that is also based on “Perfect” data collection locations. Over my career, I have collected data on some machines in less-than-optimal locations, and some would have cringed at the locations, but it gave me data I could work with.

I also understood the impact the location would have on my data and took it into consideration when I was setting alarms and looking at the frequencies the data showed.

The Impact of Sensor Placement on Data Accuracy

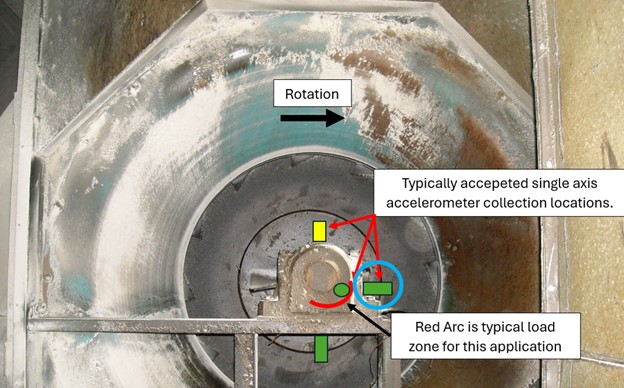

Regarding most vibration education, we are told, “The best place to collect vibration data is in the load zone in line with the center line of the shaft.” Many times, the load zone of a bearing will be between the 4 to 8 o’clock position with rotation.

The first hurdle you produce is the axial reading because you cannot get any data in line with the center line of the shaft, so that will be adjusted even when doing route-based programs.

The best place to collect vibration data is in the load zone in line with the shaft’s centerline—but access is often the real challenge.

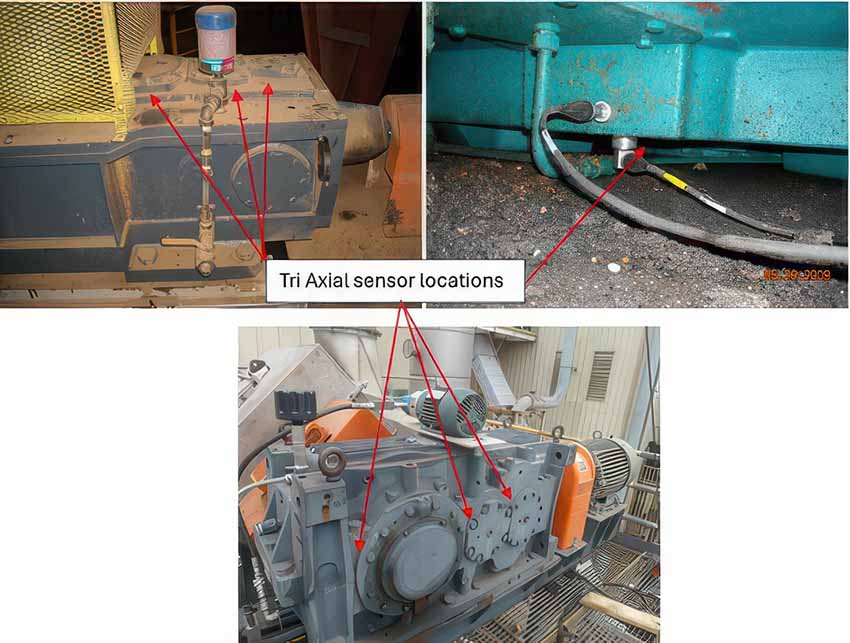

The second hurdle you face is the vertical data. Since most of the assets we work with are mounted and bolted down, like in Figure 1, getting access to that location is unlikely.

In the end, the typical data locations using single-axis accelerometers will be at the green square location in the horizontal direction. Still, the vertical will typically be moved to the yellow square location. This setup is widely accepted as a quality setup and included in standards.

Figure 1: Typical optimal vibration transducer location.

Let us discuss how you would collect this data using a triaxial sensor. In Figure 1, you will see a light blue circle. This is where it would be best to collect data using a triaxial sensor for this application, as it is close to the load zone.

Challenges of Triaxial Sensor Placement and Vibration Transmission

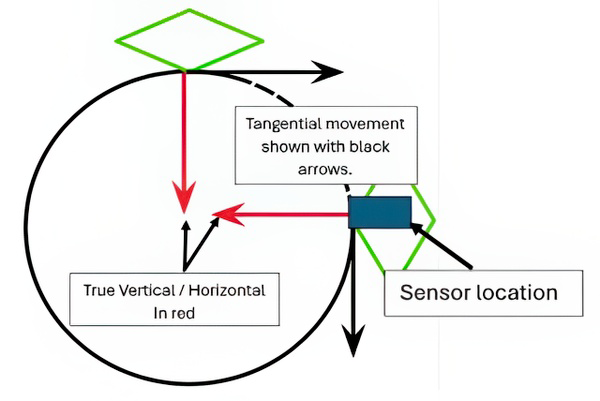

Now, let us discuss how this triaxial location will affect your data, which is where the challenges to quality data begin. When using triaxial sensors, you will encounter the phrase “tangential” to describe the radial location. This is sometimes a new term for many.

Triaxial sensors can’t always align perfectly with the shaft, leading to amplitude errors and misinterpretation of data.

Figure 2: Understanding the tangential direction.

Let’s discuss the location of the triaxial accelerometer and how it will affect the vibration levels we see in our data. In the example shown in Figure 2, the vibration data in the vertical direction would be collected along the side of the bearing.

The data will be on the edge of the bearing, so it will be somewhat attenuated, much like if the vibration had to jump across a mating surface like a bearing housing split. Based on our vibration education, we understand that high-frequency data degrades much more when this jump happens than the lower-frequency data.

Figure 3: Representation of vibration transmission.

If we look at Figure 3, the defect is along the bottom of the bearing in the location of the ‘defect area’ box. The single axial sensor would typically be placed at the top of the bearing in line with the red arrow. Although the amplitude caused by the defect will be slightly attenuated, everyone would generally say this is okay because it is the best we can get without modifying the frame to allow contact with the bottom of the bearing.

Suppose we have the triaxial sensor mounted in the location shown in Figure 3. In that case, we will see a different amplitude in the vibration because of the normal way the vibration amplitude dissipates as it gets further away from the source. Also, in this case, we are collecting data on the edge of the stress waves.

The arcs in Figure 3 attempt to show how the vibration would travel from the source of the defect to the sensor as a vector. As an end user, the critical part is understanding what is going on and how it will affect the amplitude. This example is an attempt to show you will not get the true vibration traveling in the vertical direction by collecting the data off the side of the wave.

The vibration wave is not a straight line, so there will not be as much pressure created on the side of the wave, which will cause the sensor to respond perfectly in the vertical direction. For this reason, we cannot apply every rule we have that is based on absolute vibration amplitude.

If you do mechanical IR surveys, think of this like when you do an IR scan of a bearing. The temperature you will see on the bearing housing will be less than the actual temperature that would be seen on the actual bearing race. If you want the actual bearing temperature, you would need to use a probe that contacts the outer race, as we do with sensors on some applications.

In an evaluation of remote wireless sensor use, single-axis readings were obtained right next to the sensors that were trialed to compare the data to what was collected with a route-based triaxial sensor. The chosen sensor showed almost identical data to the route-based single-axis sensor, and the temperature matched an IR image for the same location.

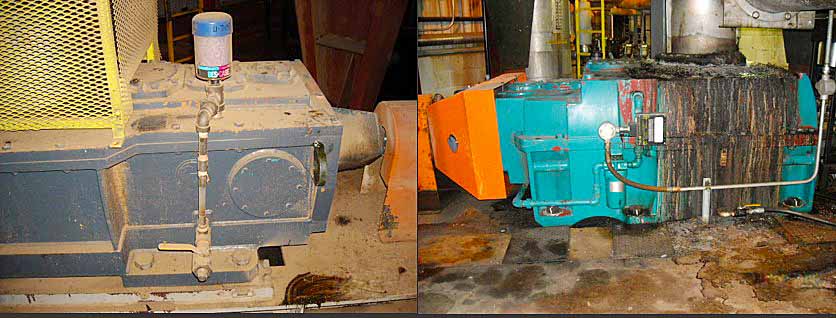

Figure 4 shows two vertical output gearboxes. To get accurate radial vibration data on the bearings, you need to be between 18 and 24 inches from the bearings in some locations and directions across the width of the boxes.

To get radial data over the length of the box, you just cannot get any high-quality data on the intermediate shafts. However, installing a sensor right next to the bearing allows us to get data in all three directions.

Figure 4: Vertical output gearboxes.

In Figure 5, the image on the left shows how data was collected on the bottom bearing of the gearbox using the duel channel process. The radial data set was collected about 18 inches from the actual shaft. A significant amount of vibration energy has dissipated by the time it gets to the sensor.

The image on the right shows how far you would be away from the intermediate shaft in the red circle if we collected one radial reading in the location of the red dot. If we take data off the bearing cover, it would be data but not 100% accurate regarding the amplitude.

Figure 5: Left dual-axis data collection and right is the potential distance from the intermediate shaft.

In the following example in Figure 6, this mill bearing does not have a way to get vertical vibration data by connecting directly to the bearing block outlined in the red box.

Figure 6: Accessibility issue for vibration transducers.

Figure 7: Possible triaxial sensor solutions.

Best Practices for Sensor Installation and Data Collection

Using the wireless sensors and either a stud mount or an epoxy mount, we can collect quality data, and it will also be repeatable because the sensors are permanently located. You would never use a magnetically mounted remote sensor for a permanent application. It is too easy for them to be knocked off during normal process and maintenance operations.

It can be easily replaced but may not be reinstalled correctly if someone does not understand the original orientation. This will have an enormous impact on our trend. When running routes, all locations must be marked to eliminate some of the issues with repeatability. Some organizations and technicians are not marking their data collection locations, which impacts repeatability.

Regarding high-frequency data showing the earliest machine defects, if you move the sensor even a fraction of an inch in some instances, there can be a significant impact on the vibration amplitudes.

Ultimately, whether we are doing route-based work or online data collection, we must first concentrate on collecting data as close to the optimal location as possible.

We must understand the impact on the vibration data when it has to cross machine mating surfaces. We should never be collecting data on motor cooling fan covers, sheet metal guards, flat metal bearing bore covers, or the center of motor stators, for example. I have seen all these happen over my career.

A sensor’s mounting method determines data quality—never use a magnetically mounted remote sensor for a permanent setup.

In Figure 8, you can see a typical center-hung direct drive pump. We should collect data in the vertical, horizontal, and axial directions. The yellow dots are some examples of locations where we should never mount a sensor.

This is an example of what is commonly observed. The red rectangles show the recommended locations to collect pump-bearing data. The best location will be on the bottom of the bearing housing, where the typical load zone of these machines is.

Figure 8: Yellow are poor locations and red are recommended locations.

Figure 9 shows a typical conveyor drive using a scoop-style motor mount. You can see my yellow marks where I collected my route-based vibration using a 2-pole magnet. Since the motor has fins on the stator and end bells, your best radial locations will need some help to set up. You can machine off the fins, but that will not be a realistic option in the field. So, you will need to use the next best option.

Figure 9: Conveyor motor with fins on all locations of the motor.

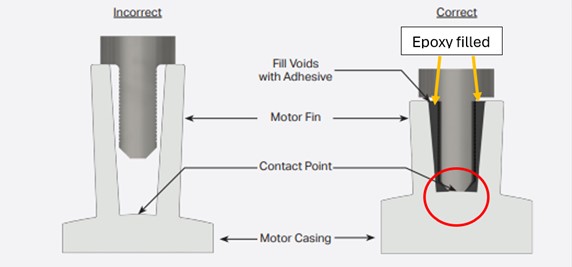

On the drive end of the motor, if you are going to mount a sensor here, a Fin Mount adapter may be applicable. However, if that is what you will use, it is critical to mount it correctly. There are times when these were used but not mounted correctly. Figure 10 shows how to install these fin-mount devices properly.

The key for these types of mounts is that they need to contact the base of the stator, as shown in the red circled area. They are not on top of the fins, as some people have mounted them, as shown on the left side of the image. Then, the area around the stem needs to be embedded in epoxy.

If you look closely at the correct image, you will notice a slight gap between the adapter and the top of the motor fin. This ensures the stem rests on the motor stator housing body.

Figure 10: Example of one transducer manufacturer’s (CTC) fin mount adapter.

Figure 11: Marked Location and passing through fan cover.

As seen in several of these images, getting access to the actual end bell bearing comes with some challenges if we talk about the motor’s non-drive end. Figure 11 is an example of how to gain better access to high-quality data. However, doing this takes time and commitment to set up.

Cutting these holes in the field can be a challenge for some manufacturers, especially for larger motors. When it comes to the cast iron cooling fan covers, it can take 10 to 15 minutes to bore the holes using a hand drill and a carbide hole saw, and it is not a lot of fun.

Figure 12: An example of how to re-cover fan cover vibration access ports.

Some plants have safety concerns about boring the holes in the cooling fan covers. They feel that an open hole would allow someone to put a finger in there and get hurt by the fan. The hole, when located correctly, is well away from the fan.

Figure 12 shows the hole cut. Then, I used an electrical box with knock-out hole fillers to cover the hole. The middle image shows the plug and the right image shows the plug that has been installed.

How to Evaluate and Interpret Vibration Data Trends

Let’s discuss how you can rate your vibration issues based on the “Rate of Change.” When you install these remote sensors, you need first to understand how the locations will impact the quality of the data we collect. We need to understand we will not always get to install a sensor in the perfect location.

As we discussed earlier, we should never install sensors in poor locations. After that, we must educate the sites/customers on how sensor locations will impact our data. Just like when we were running routes, and we requested sites to modify guards to allow us access to the bearing locations.

Triaxial sensor orientation impacts vibration amplitude—horizontal and vertical mounting yield different readings.

Figure 13A Figure 13B

Once we have our sensors installed, we need to understand how the collection location will impact our data, then adjust our analysis thinking as we review our data.

- Triaxial sensor mounted in the horizontal or vertical orientation will impact some vibration amplitude levels.

- If we look at these 2 images, one is mounted horizontally, and the other vertically. Both examples show the non-drive end sensors mounted on the end bell by cutting the holes in the cooling fan cover. The best location for these sensors to be mounted.

- In Figure 13A, the vertical data will not be 100% accurate because of the location. In Figure 13B, your horizontal data will not be 100% accurate. However, if you compare data using a single-axis accelerometer to these same readings, it is still quality data we can use.

- If the vertical and horizontal data have a ratio of 3 to 1 or larger, we could have a resonance issue that needs to be investigated.

- There will be an amplitude impact if we mount the non-drive sensor in the vertical orientation and the drive end sensor in the horizontal orientation.

- One sensor would be considered true vertical and horizontal tangential, and the other is opposite. I cannot tell you exactly how much of an amplitude impact this will have, but it needs to be considered.

- The tangential amplitude will always be impacted to a certain degree, and I feel this will differ from machine to machine.

- When mounting any sensor, we need to get it mounted as close to a bearing as possible, and if we are only mounting one sensor, we need to get it as close to a bearing as possible.

- Do not mount a sensor in the middle of the machine, thinking it will give you quality data on both bearings on that shaft. It will give you low-quality data on both bearings.

- Mount your sensor as close to the actual horizontal or vertical axis as possible.

- Always try to never mount a sensor at an off angle like 45° when possible. If you do understand how that location will impact the amplitude seen in the data.

- Monitor your frequencies of interest for change and rate of change.

- There will be times when the amplitude of a bearing frequency may be extremely low because of the mounting location. Remember that frequency should not be there.

- Understand that as long as the sensor has not been moved, and the amplitude has doubled there is an issue. For example if there are several harmonics spaced at 3.1 orders but nothing over 0.009 in/sec. Then over a three-week period it shows peaks in the 0.018 in/sec range there is a substantial change happening in a truly brief time and it needs to be addressed.

- Absolute vibration amplitude levels will only apply to one direction, whichever is in the true orientation. The other will be a representation of the vibration frequencies and amplitudes.

- If the frequencies are there, something is causing them, which is important.

- Bearing frequencies only show up if there is an issue.

- Gear mesh, vane pass, and others in this group of frequencies will be there. Changes in these frequencies’ amplitudes and patterns are reasons to be concerned.