In mid-November 1984, I entered the US Navy as a prospective electrician through the Chicago MEPS station. Coming from the Chicago Western suburbs, I was sent to the Great Mistakes boot camp, known to civilians as the Great Lakes Naval Station.

This was shortly after the anti-nuclear protests of the prior summer, which we were informed of and told not to interact with civilians and news organizations that may ask questions. There were several highlights of that period, including being put in charge of a platoon; I don’t know why; and being terrible at chewing gum and walking.

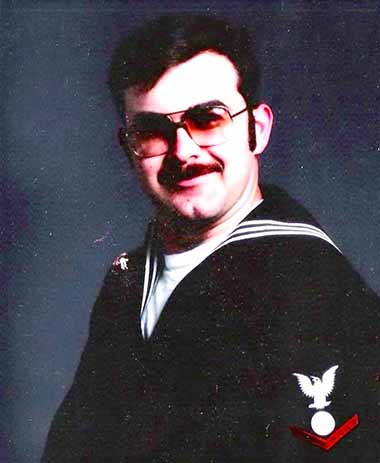

1989 when I still had hair.

However, they did keep putting me in group leadership positions while the other platoon leader was a returning Marine who decided he wanted to be a corpsman and provided some guidance for me.

Other than boredom, my fondest memory was that we were allowed to watch the Bears win the Super Bowl in 1985. Because of the deep freeze that year, we did not have the opportunity to do many of the things that you would experience in boot camp. I didn’t even fire a gun during my entire military experience.

From Boot Camp to Basic Electronics

Once I was out of basic, I was first assigned to Basic Electricity and Electronics. Because I lived nearby, I was given the position of division officer secretary and occasional bus driver, so I did not have to stand weekend watches. The training was exciting, and we often worked and trained with members of foreign militaries who were given access to our education.

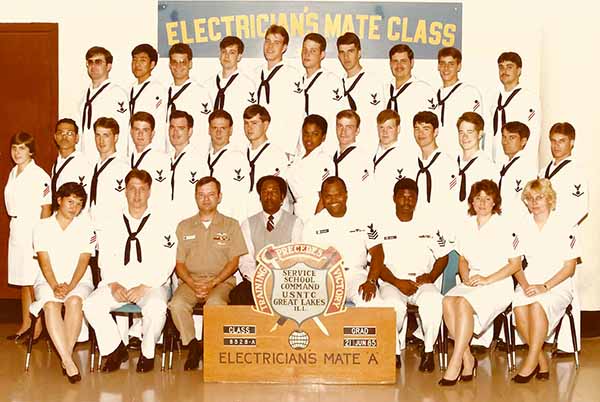

BEE (b-double-e) involves basic electrical/electronic theory, electrical measuring tools, advanced tools such as oscilloscopes, and troubleshooting by dividing the problem step-by-step and using critical thinking. Then came A-School, where I advanced to E-3 (Fireman – which refers to engineering) and graduated as an E-4 (Electricians Mate 3rd Class Petty Officer).

I did well with several others who had also been in boot camp with me but opted to remain in a conventional versus nuclear rate. I was asked where I wanted to serve, so I asked for an ocean-going tug on the west coast. I grew up in Newfoundland, Canada, and had seen way too much of the Atlantic.

While it wasn’t what I wanted, it was what I needed.

So, my orders were cut, and I headed to Newport News, Virginia, to be one of the first sailors on the USS Theodore Roosevelt, CVN-71, the largest aircraft carrier under construction then. Yep, the exact opposite of my request. However, as with most things in life, while it wasn’t what I wanted, it was what I needed.

Electricians Class USN-1

Upon arrival, I was asked what workshop I wanted to attend. As one of the first electricians on board and realizing that I performed only reasonably on motors and generators in A-school, I asked for the motor repair shop, which was designated as EE04.

I picked up a mentor, an EM2 Phillips, who spent time training me in motor connections when we were not performing inspections following shipyard work. During lull times, I was given the opportunity to attend many Navy schools, such as 8mm projector school, in which I believe mine was the last class as we were in the time of VHS tape, but it was exciting!

I was also tasked to oversee the delivery of equipment from storage to the repair shop and put together the quality assurance packages, as no one else wished to do it. That gave me specific exposure to Captain Parcells, who would later nickname me the ‘MotorDoc,’ as he had to sign off on all deficiencies, and there were, as much of our equipment was not delivered to the ship.

The Making of MotorDoc: Technical Expertise & Military Experience

During one of these meetings, the captain asked me what I wanted to do with my Navy career, and I told him I wanted to know more about electric motors. I found them fascinating. The result was that he sent me to motor rewind school in early 1987 and, while I was there, meritoriously advanced me to E5 or Electricians Mate 2ndClass.

I had already qualified for several watches, including roving electrician, aft steering, and electrical watch, in which we oversaw lockout/tagout, work orders, etc., alongside the nuclear team in ‘central control.’

Once I returned from rewind school, I was immediately allowed to perform my rewind journeyman qualifications while also providing input to the Navy’s motor rewind manual. This introduced me to a future employer, Dreisilker Electric Motors, Inc., while I was evaluating winding stripping methods.

Theodore Roosevelt during shock trials.

Many adventures were associated with my time in the Navy, both on board and when we visited a few locations. I’ve told many amusing stories in podcasts, but the historical stuff I saw included the Roosevelt being the first ship to have a co-ed aircrew.

We all welcomed it, but it was also a huge adjustment from an all-male crew, primarily in how you moved through the ship due to restricted areas (i.e., women could not pass through men’s berthing and vice-versa). We also hosted senior military officers from the USSR (that was the Russian block for you younger folk) and gave them their first close-up of air exercises.

The F-14 was scary enough, but it was the first time many of them could see the F-18 in action, and the Roosevelt was the first carrier in which all of the catapults could manage the new fighter/bomber.

There were a lot of long-term bonds that were formed between many of us on the ship. In addition, especially during the last of the Cold War, there was also a bond among us when we were in the civilian arena. It was also fun going home and actually wearing your uniform, as there was a great deal of respect for those who served, as there is now. This has not always been the case.

There were also a few port visit adventures, technical adventures, and more that serve me to this day.

Transitioning to Civilian Life: Challenges & Triumphs

One of the interesting adventures, though, was leaving the military even after only four years. It was a bit of a shock, as I’ve heard others describe it. I mean, it wasn’t terrible embracing the suck of dealing with the chaos of civilian life.

Additionally, I received military education benefits both federally and through the Illinois Veterans Act program. However, getting used to a lack of instructions, a different style of company leadership, and the post-service cruds. I think I missed most of the first two weeks of my first job.

I ran into this right away, and I was lucky that I had been promised a job in writing. The winding supervisor for the repair shop I applied to as a winder was asked by human resources to interview me. I sat down with him and responded to every question about how to connect every type of motor winding he threw at me.

I did not realize that most relied upon connection books, we had to memorize everything or be able to puzzle it out. At the end of the interview, he told me that he would tell leadership that I wasn’t qualified. I was horrified and asked why. He said I would have his job (note that I was later his boss).

So, they put me in the mechanics department, where I was also exposed to field service work. I understood testing, had unique thoughts on troubleshooting, and was later allowed to do machining and welding.

There was something about the difference between the civilian and military employees, including those who served in foreign military. There was a drive to learn, keep busy, find things to do, and always stay active.

Other workers did not always view it kindly but generally provided openings for moving up. This was another experience we learned early in the military that people would not come to you to offer advancement. You had to take the steps necessary to climb the ladder.

Yes, there was lots of help, such as reminding everyone when the rating exams were coming up, but you had to do the qualifications, study, and do the other tasks to advance in rate. Otherwise, you were generally ushered out of the military if you did not show ambition.

While in the military, I had the time and the ambition to learn and explore. When we were idle, I would also assign my team to work with other departments or practice winding dummy motors – basically, train, train, train. We also had to understand and implement the 3-M program for the Maintenance and Material Management System.

At the time, this paper program provided the groundwork for my understanding of such things as CMMS systems, scheduling, and reliability programming. This even assisted when the company I worked for went after our ISO 9002 qualifications in 1994.

I was also working with the US Department of Energy, funded by my employer, to participate in the EPACT92-inspired challenge programs such as the motor challenge.

We were also involved in motor repair efficiency work. I worked with the local and international chapters of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc., participating in standards development and chairing the Chicago Section of IEEE from 1997-1999.

Because of my combined experience and education, the company would often ask me to design or redesign electric motors, and the field service and engineering team I led also pushed the edge of using computers to accomplish our tasks. This also led to the creation of the first website in the electric motor repair industry, along with an administrative assistant who would later head up IT.

From Industry to Academia: Expanding Horizons

All of this experience then exposed me to the idea of exploring academia. So, I started teaching industrial safety at the University of Illinois at Chicago. I later joined as an adjunct professor of industrial engineering and a senior research engineer of the UIC Energy Resources Center.

While awaiting my appointment, I was exposed to machine learning, including neural networks and VRML work. At the time, the client of the consulting company I worked for was doing fly-throughs of food processing, and my team came up with simulating faults and corrective measures. In effect, these systems were early steps toward digital twin systems.

I also leveraged my time at UIC to complete my PhD in industrial/general engineering with the original intent of continuing my career in academia. However, a few things helped me decide it was not my cup of tea (coffee). I preferred doing the type of research and investigations in industry – then later for myself in my own company – that I could not do without a grant in academia.

I can honestly say that my time in the Navy, even though it was only four years, provided the background necessary to make myself independent enough.

In fact, the concept of volunteerism continues with my work in standards development and professional society participation and leadership.

I like to think I improved a bit since being a poor platoon leader in basic training. My experiences with the 3-M system and organized maintenance allowed me to take the chaos of the companies I worked for in different leadership positions to new levels of success. Even in my present role as a consultant, the basis of that work continues in the reliability side of what my company does.

A Message to Veterans: Leveraging Military Experience

Many of the leaders of the industries I participate in have been either civilian-side military or military (you’re never former). They are often the leaders or up-and-comers in an organization. The good news is that we are seeing companies take a preference for hiring veterans, and more and more veteran-owned businesses are coming into being.

For those entering the civilian world from the military, welcome. You have a unique perspective and will face some resistance because you have certain experiences that the interviewers may not have. While I left the military a week before I started working at my first post-military civilian job, in hindsight, I should have taken some time off and worked through the adjustment.

Unlike the military experience, detailed instructions are usually not available, especially in the reliability and maintenance industry. The camaraderie of the military and safety nets tend not to be present on the civilian side, hence the number of veteran support organizations.

The good news is that there are a lot of us who have had the same experience. You will realize that the brother/sisterhood still exists once you enter the civilian world and run into others who have had similar experiences. We tend to support each other in the reliability and maintenance industry.