What I’m about to say may sound like heresy. I’ve spent my career championing condition monitoring and condition-based maintenance (CBM), and I firmly believe in their value. But it’s time to get honest about the overuse of one number: 89%.

We’ve all heard it: “Eighty-nine percent of failures are not related to age or usage.” It’s cited like gospel in training rooms, boardrooms, and conference presentations. And while it’s technically accurate—in the context it was developed—it’s dangerously misleading when applied universally.

The 89% stat changed aviation – then distorted maintenance everywhere else.

The 89% figure comes from the landmark 1978 study by Nowlan and Heap, conducted for the U.S. Department of Defense. Their analysis of aircraft components revealed that only 11% of failures followed a predictable wear-out curve.

The rest were early-life, random, or condition-dependent. That insight formed the foundation of Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM)—and it transformed aviation reliability.

But here’s the catch: aircraft are not haul trucks, crushers, slurry pumps, or SAG mills.

One Number, Many Contexts

We’ve let a powerful industry-specific truth metastasize into a universal doctrine. In doing so, we’ve distorted maintenance strategy across industries where the failure curve looks very different.

We’ve mistaken a powerful truth for a universal one—and it’s cost us.

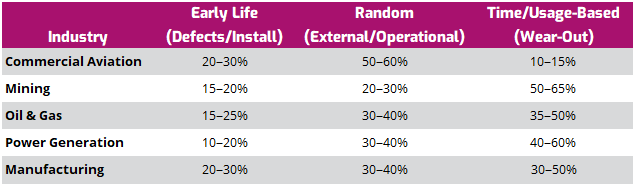

Here’s a more grounded breakdown of failure patterns by industry:

Table 1 – While a small minority of failures are age-/usage-based in commercial aviation, it’s not the case for mining and other industries.

Mining, for example, is dominated by wear-related failure modes: abrasive wear, metal fatigue, cavitation, and corrosion. Pretending that only 11% of failures are usage-based in this environment is not just incorrect—it’s irresponsible.

Time- and Usage-Based Maintenance Isn’t the Enemy

In some circles, it’s become trendy to dismiss time-/usage-based maintenance as outdated or simplistic. But the truth is, time-based maintenance—when properly designed—is a cornerstone of reliability.

It’s also:

- Administratively elegant: easy to plan, schedule, and staff.

- Predictable: tied to known operating intervals or production volumes.

- Standardizable: ideal for codifying across fleets and plants.

This becomes especially effective when time-/usage-based tasks are embedded in Life of Physical Asset Plans (LoPAPs) for each asset class.

Example: The Jaw Crusher

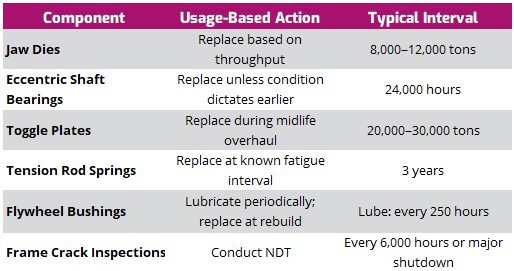

A well-constructed LoPAP for a jaw crusher might include:

Table 2 – An excerpt from a sample LoPAP for a jaw crusher in the mining industry.

These intervals aren’t guesswork. They’re derived from failure history, physics of degradation, and operating environment. They offer repeatable discipline, reduce variation, and support proactive execution.

Let’s stop acting like using time-based intervals is “less evolved.” When grounded in real-world data and managed through LoPAPs, it’s one of the most effective strategies we’ve got.

“Sweating” Assets? Tighten the Watch

Sometimes we make an informed decision to run an asset beyond its LoPAP-defined life. Maybe CapEx is constrained. Maybe the replacement isn’t ready. Maybe we’re squeezing out just one more quarter.

That’s fine—but only if you increase monitoring frequency as you enter that high-risk phase.

As risk goes up, interval goes down.

For example, if you’re pushing eccentric shaft bearings past their 24,000-hour norm:

- Move from monthly to weekly vibration checks.

- Monitor bearing temperature daily during operator rounds.

- Confirm lube film integrity more frequently.

Same goes for jaw dies: increase visual inspections and wear tracking cadence. Sweating the asset doesn’t mean flying blind—it means putting the asset on a shorter leash.

The Takeaway

- The 89% figure? Valuable in context. Dangerous outside of it.

- Condition-based maintenance? Critical—where it makes sense.

- Time-/usage-based tasks? Still the backbone of smart maintenance—especially when grounded in LoPAPs.

- Sweating assets? Fine—if you tighten your monitoring controls.

Let’s stop using a 1978 aircraft maintenance study to dictate strategy for today’s mining, energy, or manufacturing assets.

Precision comes not just from tools and sensors—but from wisely applied judgment.

Leader’s Call to Action

If you’re a leader responsible for asset-intensive operations, it’s worth asking:

- Do you know which of your failure modes are truly random—and which are wear-out?

- Are your time-/usage-based tasks based on actual asset behavior—or inherited practice?

- And when you choose to extend life, do you tighten control—or just hope?

The answers lie in structured thinking, field-proven norms, and a disciplined approach to planning. For some organizations, that starts with a class-based Life of Physical Asset Plan (LoPAP)—one that blends usage-driven maintenance with precision condition monitoring and targeted inspections.

If you’re thinking about how to build that foundation, you’re not alone. Many are rethinking how they define “best practice” for the real world—not just the ideal one.