Properly conducted RCAs are time-consuming and resource-consuming, so when we are not getting the expected ROI from our efforts, we have to consider why we are wasting so much money doing the same thing over and over again. Understanding the commercial and process factors undermining RCA effectiveness is crucial, as they can impact both the corporate bottom line and workplace safety.

A Common RCA Failure in Action

We experience an unexpected shutdown that last 6 hours. Our threshold to commission a formal RCA (i.e., our Trigger) is 4 hours, so the condition has been met. An RCA team is quickly put together amidst the chaos of the outage, and often, the person most familiar with the process involved is appointed the RCA team leader.

While under such conditions, there is an attempt to get data/evidence, oftentimes, the efforts are not as comprehensive as we’d like them to be.

This is due to time pressures to secure the area safely and restart production, the lack of cooperation by the parties that control the data to share it at that time, time pressures to conclude the RCA, and the fact there may be no requirement to provide such comprehensive validation (i.e.-evidence) of our conclusions.

The RCA team meets for a week (on and off, as that is not their primary job), and that ‘week’ timeframe is very generous. Then, they prepare for their final presentation to leadership, seeking approval for their recommended corrective actions.

Production eventually starts, the RCA is presented and finalized, and corrective actions are approved for implementation.

The same failure occurs two weeks later, and the plant manager is unhappy.

While I made up this scenario, it is based on my three decades in this RCA space, and it’s not too far from reality in my experience. Let’s look at this one scenario and see what we can glean from it.

Why Most RCAs Are Just Expensive Rework

We would have to do another RCA in our above scenario because the failure recurred. This is akin to ‘rework’. Sometimes, we tend not to view RCAs that way, and they are deemed just as a cost of doing business. But it’s not. IT’S REWORK. If it didn’t happen again, we wouldn’t be analyzing it again.

If RCA was done right, why are we doing it again? Rework isn’t just a cost of doing business—it’s a sign of a failed process.

What does that rework really cost the organization?

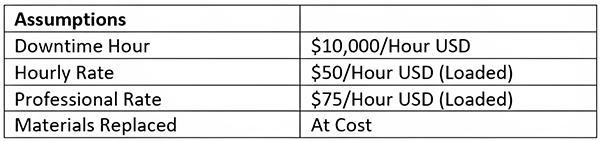

For the sake of example, let’s use the following Assumptions. For a reality check, replace my Assumptions with your own numbers and see what you come up with.

In our case, let’s assume the following resources and costs were applied to conducting the RCA:

This does NOT include ancillary costs that would involve the time of people in the storeroom/warehouse, purchasing, expediting parts, use of external Subject Matter Experts (SME), executive time for presentations, cost of implementing RCA corrective actions, RCA training and software, customer complaints, and the time of the RCA team members to meet and conduct the RCA.

Essentially, the costs in the table are to respond to the failure (not solve it). These numbers above would be safe, conservative, and very defensible.

TIP: This is important because when trying to make such a business case for rework (or RCA in general, to be honest), expect that people will try to discredit the integrity of your numbers. Ensure your numbers come from credible sources (like your accounting department).

In our very simple case, for only one recurrence, the rework will cost us nearly USD 65,000 on average. Imagine if this was a chronic failure that happened 4x/year! This is our business case to ensure we do RCA properly and prevent the risk of recurrence.

Chronic vs. Sporadic Failures: Where the Real Money Is Lost

Chronic failures are much easier to quantify in terms of ROIs. Think about why this is the case. If we have a sporadic/acute failure that happens once every 5 years, then logically, we would have to wait 5 years to see if it happens again. In other words, we’d have to wait that long to take credit for it. That’s not happening. We likely would not be in the same position five years later.

Contrast this to chronic failures that happen so often (every shift, for instance) that we don’t even record them in our tracking systems. This is usually because it may take longer to enter it into the system than it does to make the quick fix.

These failures are hidden in plain sight and often absorbed into the ‘cost of doing business’ paradigm. It’s not a failure anymore; it’s just my turn to fix it as part of my daily routine.

Chronic failures are hidden in plain sight—absorbed into the daily routine and written off as ‘just part of the job.

These are our most significant opportunities, though!! They are easier to calculate ROI because they happen so often. Our budgets accommodate them as a slush fund under something like ‘General’ or ‘Routine.’ They even get a cost of living increase every year!!

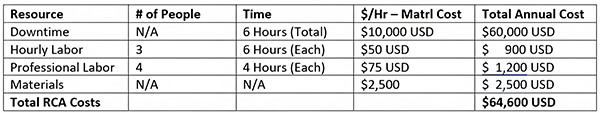

Let’s consider a simple chronic event, such as conveyor belts that trip in a mining operation. Depending on their individual impact, they may take 15 minutes to locate and reset. This 15-minute period requires a person’s attention, which at a typical standard rate ($40/hr with benefits included) results in a cost per event of $10 (0.25 hr x $40/hr labor rate).

Because the event requires a person to find and reset the tripped conveyor system, no additional parts costs are generally involved. However, the 15-minute delay causes a production loss upstream in the processing area, which equates to $5000/hr.

Fifteen minutes now is worth $1250/occurrence (0.25 hr x $5000/hr production loss). So, each 15-minute occurrence is now worth $1260 ($10 labor + $1250 lost production). It’s still considered a relatively low impact, right?

Now consider that on this particular conveying system, we experience 40 such stoppages a week, or 2080 for the year. We are looking at an annual impact on the bottom line of $2,620,800 ($1260/occurrence x 2080 occurrences). The line item in an Opportunity Analysis may look like this.

This is why our chronic failures are way more costly than our sporadic failures. Since they do not tend to hit an ‘RCA trigger’ on their individual occurrence, there is no requirement to analyze them. We just get good at continually fixing them faster. Food for thought, my friends!

Why Do We Keep Repeating the Same RCA Mistakes?

Above, we tried to illustrate the cost of rework. Now, let’s discuss why we must redo an RCA. We are doing a mini-RCA on ‘WHY RCA EFFORTS FAIL’ (more resources to come on this topic).

Isn’t it frustrating to conduct an RCA and then have the failure happen again? In my experience, when this happens, there is often an immediate rush to blame RCA (the entire acronym and field) for not being value-added. This is opposed to considering that perhaps the way in which we conduct RCA may be lacking.

“This kind of binary thinking may lead to throwing out the baby with the bathwater and wholesale rejection of traditional approaches, e.g., when adepts of the ‘new view’ reject RCA (root cause analysis) or the use of BowTies. Instead of dismissing and preaching to “stop using,” a better approach may be teaching about the limitations of approaches. Imperfect tools can be handy and are often perfectly usable within the proper context (Hale, 2014; Townsend, 2014).”

Carsten Busch, Brave New World: Can Positive Developments in Safety Science and Practice Also Have Negative Sides?

There is a stigma surrounding the acronym ‘RCA,’ and to me, it renders the term useless. This is because there is no universally accepted definition; therefore, anyone solving problems will call their approach ‘RCA.’ This can range from a 5-Why’s graphic on a bar room napkin to a comprehensive, evidence-based investigation of a serious event. Whether brainstorming, troubleshooting, the 5-Whys, the Fishbone Diagram, a BowTie approach, or a Causal-Factor Logic Tree, they are often treated as equals…and that simply is not an accurate comparison.

Blaming RCA itself is easy, but the real issue isn’t the method—it’s how we apply it.

First off, each of these approaches has its place. They wouldn’t be around for so long if some of their users were not getting a benefit. So, when properly applied, each of these tools can add value. However, the keywords in that sentence were ‘when properly applied.’

Tip: An analysis is only as good as the analyst! You can have the fanciest technology/tools in the world, but they are rendered useless if you don’t know how to use them. The tools are inanimate objects. Their users need creativity, innovation, and skill to make the tools reach their potential.

Think of artisans and true craftspeople who have specific tools for their craft and can produce masterpieces. At the same time, the general population would not know how to use the tools to create such masterpieces. I bet you can think of a hundred similar analogies where the skill of the user is what makes the tool produce ‘masterpieces.’

The same goes for RCA. How well we apply it will be the difference between success and failure. Of course, it is up to the analyst to know the tools in their toolbox and which are best to apply under certain conditions.

What’s Really Causing RCA Failures?

Here is a basic listing of what I see in the field that prevents true, holistic RCAs from providing expected value:

- RCA Process Related Issues

- RCA Methodology Less Than Adequate (LTA)

- Lacks comprehensiveness (tends to be linear in thinking)

- Lacks depth for the magnitude of the event (stops at broken parts or blaming someone)

- Lacks flexibility to apply to many different types of undesirable outcomes (not versatile enough to work for any undesirable outcome)

- Lacks evidence-based capabilities (allows hearsay to fly as fact)

- Too hard a process to follow in a practical manner (process perceived as too complex and complicated)

- Too many steps to follow (process perceived as too time-consuming, too many steps)

- Too challenging to track the effectiveness of the RCA (not easy enough to prove if it’s working or not on the bottom line [effectiveness])

- RCA Training LTA

- Training quality LTA

- Vendor instructors LTA for industry they are teaching in

- Vendor instructors inexperienced in the RCA method they are teaching

- Facility instructors are inexperienced in the RCA method they teach

- Student quality LTA

- Students did not volunteer, but were volunteered to participate

- Students’ skill sets are mismatched for analytical type work

- RCA Implementation LTA (trained students did not implement properly)

- Management support systems not in place (no systems/guidance to follow and no oversight to assist)

- Analysts too busy to do proper analysis (time pressured/shortcuts taken on RCA process)

- Too much time lapsed from the training until they were applying their new learning in the field

- RCA Champion Related

- Executive RCA performance criteria not communicated effectively to RCA Champion

- Champion did not allocate extra time for analysts to do RCA in the field (they’re too busy being reactive, no time provided to be proactive)

- RCA recommendations not implemented in a timely manner (or at all)

- RCA recommendations implemented but not effective (wrong corrective actions)

- Champion does not help field analysts remove barriers (like getting inter-departmental cooperation)

- Champion does not provide analysts engineering resources to validate hypotheses (like providing access to a metallurgist to analyze failed parts)

- Champion does not have time to mentor RCA analysts

- RCA Executive Expectations Related Issues

- No RCA expectations set from leadership

- RCA is viewed as a low priority overall

- RCA expectations were set but not communicated effectively

- No RCA Champion designated to oversee the process, OR

- Designated Champion LTA

- Champion not supported by management, so they are not motivated

- The selected champion’s skill sets are not a match for the position

- RCA expectations are viewed as unrealistic by Champions

- Champions and analysts not involved in setting expectations

RCA Done Right: The Path to Real Problem Solving

- RCA rework is astronomically expensive, and we shouldn’t tolerate it. RCA rework should be a key metric we track when measuring the effectiveness of our current RCA effort.

- From a Total Annual Loss (TAL) perspective, chronic failures are significantly more expensive than sporadic failures.

- Chronic failures will yield a much quicker and greater return (ROI) if they are the focus of an RCA strategy (similar to Defect Elimination strategies).

- There are many reasons why ‘RCAs’ may not be effective.

As the quote earlier states, ‘Don’t throw the baby (RCA) out with the bathwater,’ and just blame RCA in general. In most such cases, it is not the RCA methodology that failed. It is its proper execution that failed. If execution is the problem, it doesn’t matter which RCA approach you pick…it will suffer the same fate!

If RCA keeps leading to rework, you don’t have a root-cause process—you have a recurring cost problem.

There are ways to assess the effectiveness of your RCA initiative quickly, and I’d enjoy discussing those ways with you. I hope you found value in this content and that the concepts hit a chord with what you see in the field.

If you’d like to discuss anything RCA-related, just drop me a line at blatino@prelical.com. If you want training on these practical approaches, please check out our website at https://prelical.com/services.