One of the most important aspects of any condition-based maintenance program or maintenance inspection is knowing the optimal frequency of performing the tasks. This was part of the development of statistical tools stemming from the US military starting in the 1940s and the airline industry in the 1960s.

United Airlines developed a structured program to get through the maintenance requirements for the Boeing 747 under the guidance of F. Stanley Nowlan and Howard F. Heap.

Following this success, the Office of Assistance Secretary of Defense contracted United Airlines to publish a ‘Reliability-Centered Maintenance’ document in December 1978. By the 1990s, the principles and processes brought about by ‘RCM’ had been adopted by the power industry and NAVSEA through military and industry standards. Various methodologies that follow the framework have come into being across most government organizations, from NASA to FEMP and IEEE to IEC.

RCM revolutionized maintenance by focusing on failure modes and effects analysis.

John Moubray expanded the original RCM process to focus on aviation and published RCM2 in 1991. The goal was to bring the principles of RCM to industries like manufacturing, utilities, oil, and gas.

Understanding the P-F Curve: Origins and Evolution

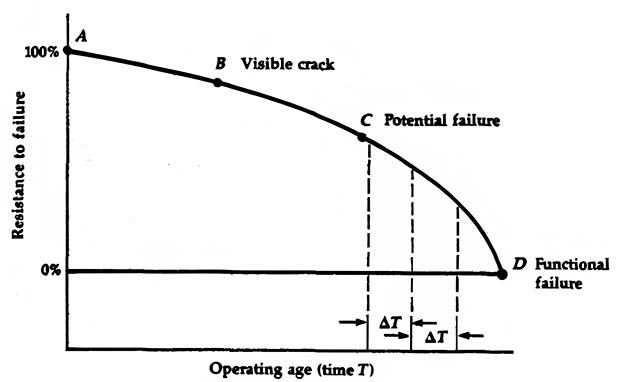

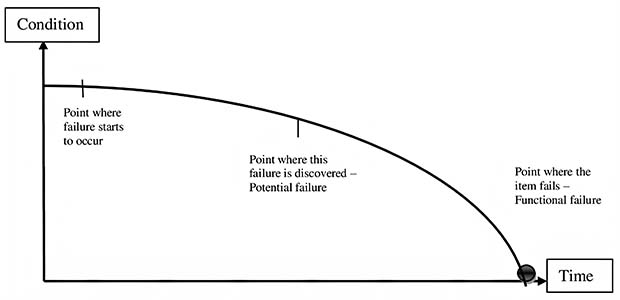

The P-F curve started with the original RCM guide in 1978 (Figure 1), which was used to establish how you determine the frequency of testing and inspections, and the 1991 version (Figure 2) which uses the point (P) where failure starts to occur and where it is discovered before ending at functional failure (F). This is where the term P-F curve comes from.

Figure 1: RCM Version of the P-F Curve in 1978, ‘RCM’ p. 75.

Figure 2: RCM2 version of the P-F curve from a 1997 presentation of the 1991 book.

The RCM2 methodology was relied upon as the new framework for the military and US Coast Guard. The primary improvement was the RCM2 focus on the failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA), which is part of the 7-step process for RCM:

- What are the functions and performance standards of the asset?

- How does it fail to perform its functions? (Functional Failure)

- What causes each function failure?

- What happens when each failure occurs?

- How does each failure impact safety, operations, and cost? (and ‘other’)

- What can be done to predict or prevent the failure?

- What should be done if no proactive task can be found?

The tasks are categorized into:

- Predictive Maintenance (PdM): Condition-based monitoring to detect the functional failure before it occurs.

- Preventive Maintenance (PM): Scheduled maintenance to prevent failure.

- Corrective Maintenance (CM): Reactive maintenance after a failure.

- Functional Maintenance (FM): Used to test and verify a function, such as a safety device, operates.

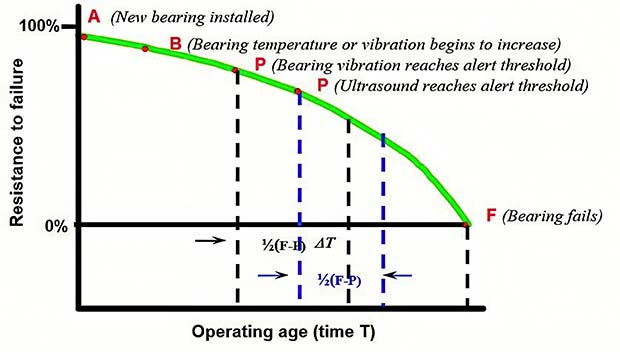

The data provided in the process identifies functional failures and the methods that can be used to identify (test or inspect) the point of detection (P) to failure (F). The original purpose of RCM and RCM2 was to take at least ½ then that time and perform testing. Other standards, depending on equipment criticality, may increase the inspection interval, such as ¼, 1/8, etc., until it makes more sense for continuous maintenance.

In 1995, I utilized a version of the P-F curve in ‘A Novel Approach to Electric Motor System Maintenance and Management For Improved Industrial and Commercial Uptime and Energy Costs.’ The version I used is shown in Figure 3 in follow-up presentations and teaching.

Figure 3: Using the P-F curve for determining the frequency of testing (Penrose, 1995) as an example.

Misconceptions and Realities of the P-F Curve

Several misunderstandings work with these curves. The original concepts come from industrial engineering and statistical analysis of different types of faults. It was meant as a quick reference point to guide RCM analysts in test frequency, and the curve follows an inverse natural log curve.

While we have seen people argue the curve as if it were engineering fact for every application, it was never meant to be such. Marketing groups and different CBM technologies have also adopted it to position themselves and show how much better their widget is than the other widget.

Of course, these assume that every application fails in the same way and that some widget can detect every single condition in exactly the same way, which does not exist.

Effective maintenance requires data-driven decisions, not marketing-driven myths.

The curve is also supposed to start once a fault is initiated. Presentations of the curve as if it represents installation to functional failure represent a very specific misunderstanding of the curve and what it is meant for.

Part of this comes from the concept of the bathtub curve, which comes from actuarial science starting in the 1600s and then insurance in the 1800s, a fundamental concept in industrial engineering risk. It was applied to all systems in the 1940s following World War II as part of the efforts to improve the reliability of military equipment.

It was later discovered that the patterns actually vary by application, type, and complexity. Most systems result in a flat-line resistance to failure until a condition occurs that triggers what we identify as some variation of the P-F curve.

These are important concepts as we have watched reliability science devolve into marketing voodoo science related to the effort to sell technology. Understanding unadulterated science becomes important for the ability to successfully select and apply technologies versus the misapplication of abstract concepts as fact.

Practical Applications: Selecting Test Frequencies for Reliability

The basic concept for selecting the minimum frequency is determining the components and failures of interest with RCM (or backfit RCM – the follow-up process) and how early each fault can be detected by different inspections and/or testing. This also means there may be instances in which one technology may detect a problem 1000 hours ahead of a functional failure and one that detects in 800 hours.

Still, the 800-hour test shows other conditions of interest, so it becomes more effective to test every 400 hours with one technology rather than adding the additional one. There are a lot of other considerations; otherwise, this task would be simple and one-off.

Understanding the reality behind how your systems fail and understanding reliability science allows an accurate method for selecting frequency and, when needed, justifying continuous monitoring or other detection methodologies. In 2007, I expanded on the concept in a paper for the IEEE Dielectric and Electrical Insulation Society (DEIS) at the Electrical Insulation Conference, in which simple calculations can be used to estimate times to failure from fault detection.

This methodology was republished in 2009 by IEEE DEIS Dielectrics Magazine – a link to a copy of the peer-reviewed paper can be found at the end of this article. You will note that a variation of Figure 3 is used in the article for electrical insulation to represent detection to failure.

Understanding your system’s failure dynamics is key to maintenance success.

The concept around TTFE is meant for small volumes of equipment and limited information, at least in this early version. The breadth of the application of TTFE for modern electric machines will be covered in future articles.

However, if we have a system with an average of some component failing within 8 weeks of fault initiation with testing or inspection tech we have available, we would want to schedule testing or inspection for the types of failures every 4 weeks. This is even if the failure occurs on average every 5 years.

For example, I have an electric machine that has a bearing failure an average of every 3 years (MTBF), and I am using an Electrical Signature Analyzer that can detect the failure within 12 weeks of failure. How often would I perform testing? The answer would be every 6 weeks. The risk of failure is considered relatively constant until some defect or condition is detected. The challenge is understanding the period from detection to failure, which will be unique to each application.

The original copy of the Nowlan and Heap can be downloaded directly here: RCMOrig.pdf (1978) from MotorDoc.com. The IEEE paper on Time-to-Failure Estimation basics can be found on the same website here: Simple Time-to-Failure Estimation Techniques for Reliability and Maintenance of Equipment (2009). Both papers may be downloaded for individual use, and the Nowlan and Heap are public and may be shared.