In asset management and maintenance, we like to think we make data-driven, rational decisions—but the truth is, we don’t. Cognitive biases pull us off track, leading to avoidable failures, cost overruns, and lost production.

I’ve been deeply influenced by the work of Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky (Prospect Theory), Robyn Dawes (rational decision-making), and John Mowen (risk perception and behavior). These researchers have spent decades studying how humans actually make decisions – not how we think we make them.

One of their key insights is this: people don’t evaluate risks and rewards logically – we weigh losses more heavily than equivalent gains.

We don’t manage assets based on logic—we manage them based on fear, habit, and hope.

Let me illustrate:

Suppose that I give you $100. Once you have the bill in hand, I offer you a bet – double or nothing on the flip of a fair coin. Most people decline. They’d rather keep their guaranteed $100 than risk losing it, even though the expected value of the bet is neutral.

Now, let’s flip the scenario. Suppose you owe me $100. I offer you the same bet – double or nothing. This time, people overwhelmingly take the bet because the fear of loss drives them to take greater risks than they normally would.

This asymmetry is Prospect Theory in action, and it plays out every day in asset management. It leads us to defer preventive maintenance, gamble with asset reliability, and avoid replacing failing equipment.

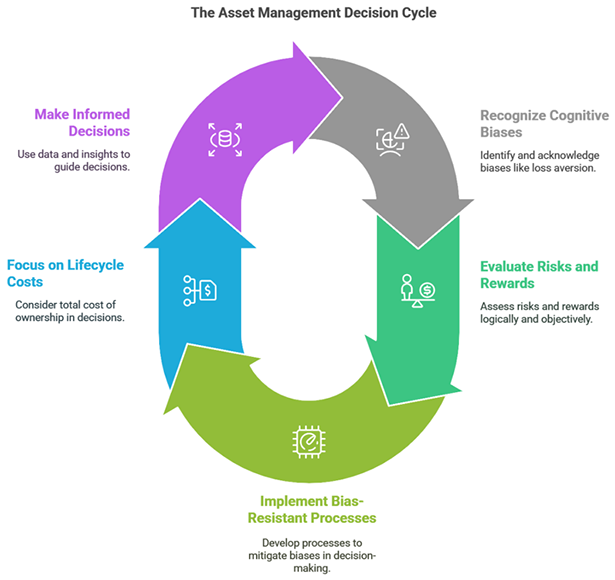

So, let’s stop pretending we’re always rational and start designing bias-resistant processes in asset management.

The Loss Aversion Trap: Why We Delay Necessary Maintenance

Problem: We fear losses more than we value equivalent gains. This is Prospect Theory 101 – the pain of losing $100 is about twice as strong as the pleasure of gaining $100.

How This Plays Out in Asset Management:

- We defer preventive maintenance because it “costs too much” or requires downtime – only to face bigger failures and higher repair costs later.

- Operators push assets harder than intended to hit short-term targets – ignoring long-term damage.

- We delay capital replacements because of the immediate cost pain – even when the total lifecycle cost proves replacement is the better option.

Now, let’s apply the $100 bill example to maintenance:

- A maintenance team has a healthy budget for asset reliability (holding the $100 bill). When faced with the decision to spend it proactively or risk a breakdown, they hesitate to risk losing what they have – so they defer spending.

- But when the team is already over budget (owing the $100), they take bigger risks, skipping maintenance entirely, running assets past safe limits, and hoping for the best – just like the gambler trying to get back to even.

Bottom line: Loss aversion makes us resist spending money on proactive maintenance – even when we know it will save us more in the long run.

Solution: Shift from short-term budget thinking to lifecycle cost management. Use Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) models to ensure you’re not saving pennies now to lose dollars later.

Ask yourself: If I don’t spend the money now, how much will I lose later?

The Bald Tire Bias: Why We Ignore Growing Risks Until It’s Too Late

You wouldn’t drive on bald tires forever. But some people do – until they hydroplane in the rain.

That’s the Bald Tire Bias – a form of Normalization of Deviance. The longer we get away with risky behavior, the more we start to believe it’s not risky at all.

How This Skews Maintenance Decisions:

- A pump is running with high vibration, but we assume it’s fine since it hasn’t failed yet.

- A gearbox has dark, contaminated oil, but “we’ve seen worse, and it ran for months.”

- A hydraulic hose is cracking, but “it hasn’t blown yet, so we’ll wait for the next inspection.”

Here’s the reality: The absence of failure does not mean reliability – it often just means you’ve been lucky.

This plays out in some of the worst industrial disasters in modern history.

- BP Texas City (2005): Warning signs of unsafe operations were ignored—until a catastrophic explosion killed 15 workers.

- Prudhoe Bay Pipeline Spill (2006): Known corrosion was repeatedly deferred—until the pipeline leaked 200,000 gallons of crude oil.

- Deepwater Horizon (2010): Red flags were dismissed as routine deviations—until the rig exploded, killing 11 people and triggering the worst offshore spill in history.

Each disaster followed the same path: Risk tolerance increased because previous warnings didn’t lead to immediate catastrophe.

High-Reliability Organizations (HROs) don’t wait for catastrophic failures – they stay vigilant to weak signals that indicate early signs of trouble.

Solution:

- Condition-Based Monitoring (CBM) – Use data, not luck, to assess asset health.

- Risk-Based Asset Renewal – Replace before failure, not after.

- No More “We’ve Always Done It This Way” – Old habits lead to expensive breakdowns.

If you’re waiting for a failure before acting, congratulations—you’re playing asset management roulette. High-Reliability Organizations (HROs) don’t wait for catastrophic failures; they stay vigilant to weak signals that indicate early signs of trouble.

The “Sunk Cost” Fallacy: Why We Keep Pouring Money into Failing Assets

We’ve all seen it: A company keeps throwing money at a dying haul truck fleet, outdated conveyor system, or failing software platform – because they’ve already spent too much to stop.

That’s the Sunk Cost Fallacy. It’s like doubling down at a casino – you’ve lost money, so you keep gambling in hopes of getting it back.

Solution: Ask yourself: “If we weren’t already invested in this, would we spend money on it today? If the answer is no, cut your losses and reallocate resources to something better.

Final Thoughts: Stop Managing Assets Based on Emotion

The biggest takeaway? We’re not rational decision-makers.

We:

- Fear short-term losses more than long-term gains.

- Ignore growing risks because we’ve “gotten away with it so far.”

- Assume past reliability means future reliability.

- Throw money at failing assets because we’re already invested.

- Overreact to recent failures instead of looking at overall risk.

The good news? We can fix this.

- Use TCO models to drive proactive maintenance.

- Base decisions on data, not luck.

- Replace assets based on risk, not sunk costs.

- Prioritize failures based on actual impact, not recency.

- Challenge overconfidence with structured analysis.

At the end of the day, bias-resistant decision-making is the key to safer, more reliable, and more cost-effective asset management.

It is time to move past gut-feel decision-making and apply the science of rational asset management.