Maintenance and engineering managers know that deferred maintenance never goes anywhere. In the last five years, many people inside and outside institutional and commercial facilities were understandably preoccupied with the fallout from the nation’s financial crisis.

Deferred maintenance never really stops—it only builds up, waiting to become a crisis.

While all that was occurring, managers were continuing to address the mounting backlog of maintenance needs many facilities have faced for decades. So, while the issue of deferred maintenance might seem like it has only recently become a problem again, managers know that it never really stopped.

Deferred maintenance is the practice of postponing maintenance activities, such as repairs on both real property — infrastructure — and personal property — equipment and systems — to save money, meet budget funding levels, or realign available budget funds.

The failure to perform needed repairs could lead to asset deterioration and, ultimately, asset impairment. Generally, a policy of continued deferred maintenance results in higher costs, asset failure, and, in some cases, health and safety problems. Consider this example:

A neighbor of mine knew the large oak tree in his front yard needed to be removed, but he didn’t have the money to hire a professional, so he let a local kid try his luck.

The young man had never cut a tree that large, had no idea how to cut such an imposing object, and in the process of trying, nearly had it fall on him. Of course, nature took care of the tree the next week when a storm blew through and laid it across the porch and two cars.

Without an aggressive, proactive approach, deferred maintenance will always win.

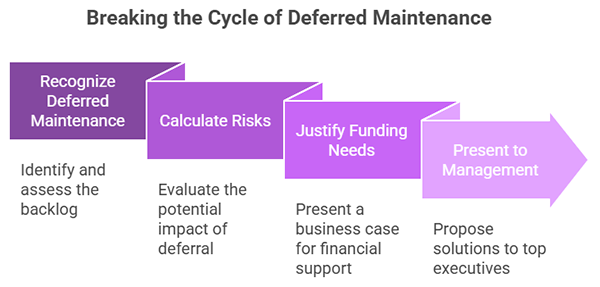

Breaking the Cycle of Deferred Maintenance

We’ve all played the game of moving money around to pay the bills—robbing Peter to pay Paul if you will. Eventually, that practice catches up to us and causes bigger problems. Underfunding routine maintenance can cause deterioration in facilities, which evolves into major work and severe conditions.

Deferred maintenance doesn’t just disappear—it compounds into bigger, costlier problems.

Deferring maintenance only adds to the backlog. When our backlog grows, we don’t have enough resources, and when we don’t have enough resources, our backlog continues to grow. The result is a vicious cycle.

Managers need to break out of this cycle of futility and gain control of the situation. Top executives must understand the risks, rising costs, and overall impact of deferred maintenance on facilities. They should present a business case and proposal to top management for funds to address the maintenance backlog before it becomes too big to manage.

Managers can take these two steps to start the process:

Recognize

Recognize and calculate the risk of deferment. Assess the true deferred maintenance backlog and the extent of its risk. This step is vitally important in validating the need for funding. A facility condition assessment of current operations and buildings can help managers identify unknown problems and provide a better understanding of the extent of deferred maintenance.

The assessment should yield a clearer picture of maintenance needs and the magnitude of the required work. Once the assessment is complete, we can calculate the associated risk and estimated costs based on the results.

Justify

Make the business case for financial planning to reduce the impact of deferred maintenance. When I was an operations manager and one of my managers requested funding without justification, a business case, or a return on investment, I considered it an emotional request, not a business need.

When we request funds to tackle deferred maintenance, it must be predicated on documented data. That data should include the following documentation to build the business case:

- Historical data. No one can argue history. If the data is captured correctly, it builds a solid foundation for justification and business-plan development.

- Potential of risk. Consider my story of the falling tree. What if that tree had fallen on a bedroom in the evening or a kitchen during mealtime? Deferring certain activities can affect safety, health, the environment, occupants, and operations.

- Cost acceleration. Managers can use several tools and software programs to calculate and predict future expenses resulting from deferred maintenance.

The next step for managers is determining what to do with the results of the assessment. I suggest taking the findings and plotting them on a matrix. Managers can use a facility condition index (FCI) as a benchmark to compare the qualified condition of facilities and to build support for asset-management initiatives.

To create an FCI, managers need to quantify the cost of maintenance, repair, and replacement deficiencies, as mentioned in the facility condition assessment earlier. This total cost of repair or replacement is then divided by the facility replacement value (FRV), which is the current monetary replacement value the organization places on the facilities.

Managers then can prioritize the results:

- Currently critical. These top-priority items are needs or projects that significantly impact the operation and require immediate action to return a facility to normalcy, stop accelerated deterioration, or correct a cited safety hazard, especially those conditions that pose a significant risk to health and safety.

- Potentially critical. These needs or projects will become critical within a year if not addressed in the short term — typically, less than a year.

- Necessary but not critical. These projects include conditions that require reasonably prompt attention to preclude predictable deterioration or potential downtime and the associated damage or higher costs if deferred further. This class falls into long-range planning when developing budgets for the next 5-10 years.

After this exercise, managers can plot the outcomes to identify the items with the highest cost or risk. They can then use the corroborated data to build the business case for immediate and long-term planning funding.

A strong business case for maintenance funding turns problems into solutions.

Most top executives do not want managers to come to them only with problems. So, to successfully attack deferred maintenance, managers need to address issues and come prepared with solutions. As uncomfortable and frustrating as tackling deferred maintenance might be, its prioritization is a hallmark of sound fiscal management.