In 1986, a facility with over 3,200 process pumps analyzed its failure data from five years. The plant found that nearly all failures, regardless of the machine, could be grouped into one or two key categories of failure causes:

- Design defects

- Material defects

- Processing and manufacturing deficiencies

- Assembly or installation defects

- Off-design or unintended service conditions

- Maintenance deficiencies (neglect, procedures)

- Improper operation.

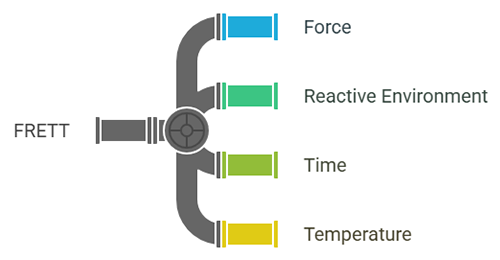

The plant reporting its failure distribution also accepted that mechanical parts could fail due to one of only four cause categories: Force, reactive environment, time, and temperature. For the past five decades, we have remembered these by the acronym “FRETT.” Forward-looking plants have taught “FRETT” to their field and shop maintenance workforces. “FRETT” is a theme worth explaining several times.

Forward-looking plants teach ‘FRETT’ to their field and shop maintenance workforces.

At an oil refining facility with 3,200 process pumps that the author often visited, the failure distribution was roughly as follows:

- Design defects 6%

- Material defects 4%

- Processing and manufacturing deficiencies 8%

- Assembly or installation defects 20%

- Off-design or unintended service conditions 18%

- Maintenance deficiencies (neglect, procedures) 32%

- Improper operation 12%.

Upon closer examination, the above statistics conveyed two critical observations:

Most pumps fail because of maintenance- and installation-related defects. Since pumps generally represent a mature product, fundamental design defects are infrequent. Reliability professionals at that facility could readily vouch for two more facts:

- Pump failure reductions were achieved mainly by appropriate action of plant reliability staff and competent plant or contract maintenance workforces.

- Contractors were long-term assignees to the plant; at best-in-class (BiC) facilities, they received the same training as regular employees.

Most pumps fail because of maintenance- and installation-related defects.

The Role of Maintenance in Pump Longevity

Based on the above failure distribution, pump manufacturers are rarely to blame. Nevertheless, it is unfortunate that not all pump manufacturers are knowledgeable in pump failure avoidance.

That is why the owners’ engineers must lead the identification and upgrading of the “weak links.” Judicious upgrading is very often possible and is generally very cost-effective. The merits of upgrading can be visualized by pondering the size of large plants.

Pump Reliability Is Independent of Plant Size

In the mid-1980s, a chemical plant in Tennessee had over 30,000 pumps installed, and a large facility near Frankfurt, Germany, reported over 20,000 pumps. However, the largest industrial pump user appeared to be a city-sized plant on the Rhine River banks south of Frankfurt. There were approximately 55,000 pumps installed at that one location alone.

U.S. oil refineries typically operate from 600 pumps in small facilities to 3,600 pumps in large facilities. Among old refineries, some had an average pump-operating time of over nine years. However, some achieved an average of only about 20 months.

Organizational mindsets and employee motivation make a difference in reliability.

Some of the very good oil refineries were new, but some in the same category were relatively old. Certain bad performers belonged to multi-plant owner “X,” and some good performers also belonged to the same owner, “X.”

Therefore, it can be said that equipment age does not preclude obtaining satisfactory equipment reliability. Organizational mindsets and employee motivation are important and will make a difference.

Reliability vs. Repair: A Critical Mindset Shift

Experience shows that facilities with low pump mean-time-between failure (MTBF) or mean-time-between repair (MTBR) are almost always repair-focused. In contrast, plants with high pump MTBF are essentially reliability-focused. Repair-focused mechanics or maintenance workers see a defective part and replace it in kind. Repair-focused plants turn their mechanics into parts changers instead of failure analysts.

Conversely, reliability-focused plants ask why a part failed, decide if upgrading is feasible, and then determine the cost justification or economic payback achieved by implementing suitable upgrade measures.

Needless to say, and always well worth repeating, is that reliability-focused plants teach “FRETT” and motivate their maintenance-technical staff. These staffers seek to implement every cost-justified improvement as soon as possible. The following reliability-focus example discusses why the power end of a pump can fail and how to avoid such failures.

Diagnosing Elusive Pump Failures

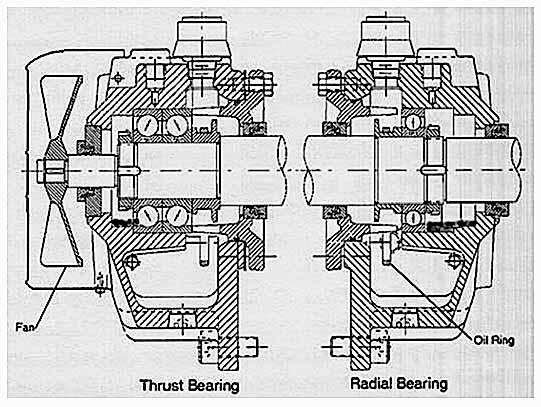

Causes of failures, elusive or not, can be discovered. Suppose the pump bearing housings shown in Figure 1 require bearing replacements. But why did the bearings fail? Answer: Lube oil trapped between the bearings and their respective end caps cannot escape. Trapped oil will overheat, and its carbon residue degrades lubricants and bearings.

Both will degrade if drain holes are missing from the picture; always insist they are provided. Unless this discrepancy is recognized and rectified by a reliability-focused owner or a competent pump-repair shop (“CPRS”), the degradation events will repeat themselves. A Short bearing life will cost the owner company and its stakeholders dearly.

While replacing bearings, you might also pay attention to Figure 2. Here, an oil ring shows substantial abrasion damage, and several contributing reasons likely exist. Cheap oil rings are not usually stress-relief annealed. Unless stress-relieved before finish-machining, they will become out-of-round and slip and skip.

Also, unless the driving and driven shafts are installed parallel to the true horizon, oil rings will run downhill and often come into contact with bearing housing-internal or cast-in components. As abrasive wear occurs, the two oil rings in Figure 2 will slow down, and contaminated oil will reach the bearings.

Both examples are among dozens that demonstrate the value of employing and retaining a well-trained workforce. Some plants practice structured and well-guided maintenance efforts; moreover, good supervisors do double duty as experienced teachers. Their work execution and follow-up inspections are well-planned and executed.

Still, other plants are remiss in allocating time, brain power, and monetary resources to these essential pursuits. Furthermore, one plant may be located in a geographic area with abundant competent repair shops while another is not.

Figure 1. Lube oil trapped between bearings and their respective end caps cannot escape. Consider this an elusive cause of bearing failure.

Figure 2. Oil rings in new (left) and badly worn (right) condition. Cheap oil rings are not stress-relief annealed; they tend to deform and malfunction. Oil rings abrade while skipping around and contacting housing-internal surfaces.

Asset Performance Starts with Attention to Detail

When the implications of Figure 1 and Figure 2 were pointed out to groups of maintenance and reliability technicians in four different countries, it was clear that fault-inducing details of this type were constantly overlooked.

It was also clear that while organizational initiatives such as Asset Management and Operational Excellence had gained prominence, attention to detail and the systematic acquisition of highly relevant in-depth knowledge remained vastly under-appreciated. When all is said and done, understanding these details is the absolute bottom line, one of the keys to asset performance.

Highly competent professionals loathe unplanned downtime and frequent maintenance.

Other keys to asset performance include design, maintenance, and operating knowledge. Each of these branches of knowledge needs to be implemented responsibly. Accountability and even-handedness must exist in all relationships among employees and their supervisors. An ethical reward system must be in place for knowledge to be practiced and implemented with unerring continuity and wisdom.

However, so as not to lose sight of the keywords “Bearing and Lubrication” in this article’s title, there are strong indications that fewer spare parts will be consumed by facilities that implement and inculcate the necessary knowledge in well-structured ways. Plants and facilities staffed by highly competent maintenance and reliability professionals hate coping with repeat failures.

These professionals view every maintenance intervention as a challenge to their desire to upgrade or design out the need for excessively frequent preventive maintenance actions. Highly competent maintenance and reliability professionals loathe unplanned downtime events and the need for too much maintenance.

They estimate the value of upgrading by making good use of information in the book from which this article excerpt has been taken and make sure weak links in a pump’s component chain are beefed up or, better yet, designed out.

The High Cost of Ignoring Root Causes

Note that only two root causes of repeat failures exist. Solid professionals agree, without equivocation, that all repeat failures must be ascribed to the fact that the root cause of a failure has not been determined or that the root cause is indeed known, but remedial action is not being pursued.

Highly experienced practitioners of maintenance and reliability improvement skills will never be at ease with either of these two possibilities, that is, not knowing what led to a failure or knowing why an asset failed and doing nothing about it. Competent practitioners view these challenges as personal affronts like a medical doctor losing a patient to the common cold.