By Howard Penrose and Eric Foreman

As maintenance and reliability professionals, we know that misalignment reduces the life of bearings and other components. Still, what impact is associated with misalignment, meeting basic alignment tolerances, and precision alignment?

Understanding the Impact of Misalignment on Motor Efficiency

This article will discuss percentages related to several potential failure points based on data collected from a 1-hp, 1765-rpm, 460V, 1.5 Amp motor operating at several load points. We’ll then compare this to a 600-horsepower motor that’s operating with a misalignment. We reference ANSI/ASA S2.75-2017, “Shaft Alignment Methodology, Part 1: General Principles, Methods, Practices, and tolerances,” for the alignments.

The data in each case is collected with an EMPATH™ Electrical Signature Analysis (ESA) system that provides a measurement of watts by defect (spectral analysis of power). The percentage of additional greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) above the total expected GHG will be included in the analysis.

The first thing was to take the test motor and evaluate it after using a ruler to align a direct-drive coupling and measure the load. The power spectra was measured and losses specific to 0.5 and 1 times rpm, static eccentricity peaks, and bearings were identified in watts lost at the defect frequencies.

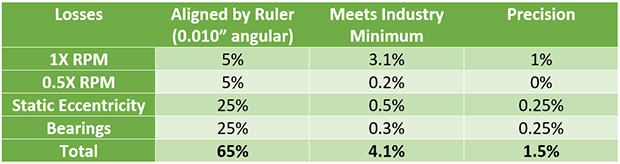

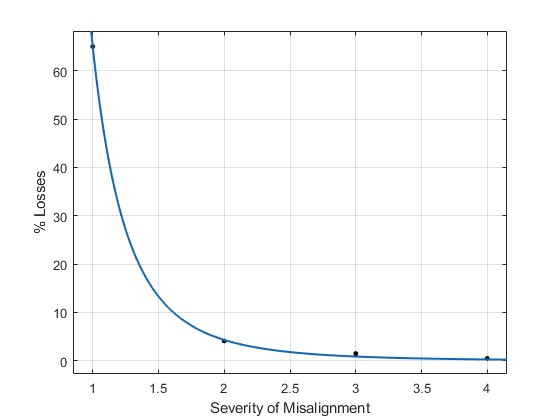

This work was performed in a lab to isolate specific defects. The second test was alignment performed to minimum industry specifications. The last test performed was “precision alignment,” which we define for this article as 25% of the tolerances for a standard tolerance. The results of all tests were calculated, as shown in Equation 1 below, and are presented as percentages in Table I. (The curve for Equation 1 is shown in Figure. 1.)

Equation 1

Table 1: Percent Losses from Alignment

Figure 1: % Losses and severity of misalignment: 1=alignment with a ruler; 2=alignment with industry tolerances, and 3=precision alignment.

Quantifying Energy Losses and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

When calculating the opportunity to reduce emissions by alignment, it was found that this opportunity follows the energy losses curve exactly as a percentage of the total energy used.

For instance, on a larger motor operating on a variable-frequency drive, vibration and ESA data identified misalignment and soft foot of a 600-hp, 460V electric motor operating 6,000 hours per year at 40 Hz, with a demand of 90.5 kW. This would translate to 543 Megawatt-hours per year at 0.707 Tons CO2 per MWh or 384 Tons CO2 per year.

To understand the complexity of separating out the losses associated with an electric machine, we first need to understand efficiency standards and calculations. The changes cited in Figure 1 are increases to the electric motor’s losses and not a direct relationship to full load. This means increased bearing friction, often measured in watts, with the values varying by the size of the ball or roller bearings.

One of the more interesting issues we’ve been wrestling with since the early 1990s is how to evaluate the efficiency of an electric motor in the field. It sounds simple, but even now, the discussion continues among academia, manufacturers, end-users, independent engineers, international energy programs, and others.

During discussions related to the renewal and re-issue of standards such as IEEE 112-2017, “Test Procedure for Polyphase Induction Motors and Generators,” opinions varied widely, based on consensus over the years (with a heavy slant by motor manufacturers). IEEE 112 Method B is one cited reference by the U.S. federal government for calculating efficiency and developing energy policy related to electric motors.

Another cited reference is NEMA MG-1 (the National Electrical Manufacturers Association Motors and Generators standard) for nominal and minimum efficiency. This makes the accuracy of the standards important to regulatory bodies and end-users while making the methods biased towards higher values important to original equipment manufacturers (OEM).

The methods for laboratory testing of motor efficiency are complex and require exact measurements at specific load points to develop a curve that allows motor manufacturers (OEMs) to determine a nominal (average) efficiency. Most OEMs will use software to estimate efficiency in an electric machine’s design and modeling stages.

The Challenge of Measuring Motor Efficiency in the Field

Why is electric motor efficiency so important? This is simple: A motor’s efficiency is determined by the energy supplied to the motor in kilowatts (kW) to the output torque at the shaft, which is converted to kW. The difference is the energy lost in core losses, winding losses, friction and windage losses, rotor losses, air gap losses, and smaller parasitic losses that all generate heat, vibration, and noise.

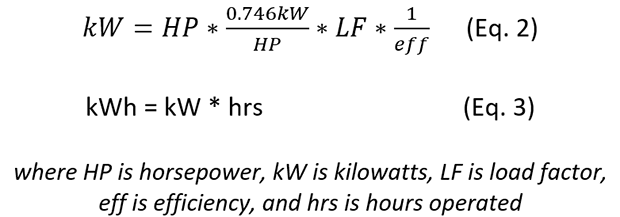

This situation directly relates to the cost of operating the electric motor, its reliability, and the motor user’s impact on greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). Once you know a motor’s efficiency, you can estimate your operating demand and usage as shown in Equations 2 and 3 below. You can also reasonably assess the reliability of your electric machines and even the effectiveness of your motor repairs.

For example, if I have a 100-hp motor operating at 75% load factor for 6000 hours, and I know the unit is 94.5% efficient, I also know it is using (100 * 0.746kW/HP * 0.75 * (1/0.945) =) ~59.2 kW and 355,200 kWh.

This is an approximation, as I don’t know the efficiency at 75% load unless I have the motor literature, use the estimated curves from the U.S. Department of Energy (USDOE, energy.gov), or have measured everything. But I can estimate. Above 50% motor load, using the full load nameplate efficiency is a reasonable estimation, as it is already up to 1% to 2% of the actual motor efficiency.

Granted, this assumes that some type of damage has occurred, or a poor-quality repair has been performed. Otherwise, the efficiency would be the same or better.

The result, if we have energy costs of $10/kW demand and $0.10 usage and use 0.707 Tons CO2/MWh (2020 national average – https://eia.gov), would be what’s shown in Equations. 4, 5, and 6, resulting in: $7,104 demand, $35,520 usage, and 251 Tons CO2/yr.

Now, if we have a poor-quality repair that impacts efficiency by 1%, then the numbers change to 60kW, 360,000 kWh, $7,200 demand, $36,000 usage, and 255 Tons CO2. This reflects an increase in operating costs of $576/year and 4 Tons CO2/year. While such numbers don’t seem excessive, they add up quickly when extended across a plant.

When attempting to determine the efficiency of a plant’s electric-motor assets, removing a unit and performing IEEE 112 method B testing, CSA 390 (Canadian) testing, or IEC 60034-2-1 testing is neither affordable nor feasible. In the 1990s, organizations, including the USDOE’s Motor Challenge program, worked on various methods for field efficiency testing.

These methods ranged from wattage tests to voltage and current to ORMEL96 (Oak Ridge Motor Efficiency and Load 96) and commercially dedicated field-testing devices.

Of particular interest, as we continue this discussion, will be the ORMEL96 methodology that traces back to the study, “Assessment of Methods for Estimating Motor Efficiency and Load Under Field Conditions” (ORNL, January 1996). Results from this method were very close to those from the IEEE 112 Method B. (Note: Many of the existing commercial ESA devices have some traceability back to the ORMEL96 method.)

Fortunately, even without a commercial device, there are methods for evaluating field efficiency using watt meters or voltmeters and clamp-on current meters, among others. The further you deviate from the torsional and standards methods, the more that accuracy will be affected. And, if you drop below 50% load, error increases.

These methods are discussed in the USDOE document “Determining Electric Motor Load and Efficiency” Determining Electric Motor Load and Efficiency (energy.gov) and the USDOE “Premium Efficiency Motor Selection and Application Guide,“ Premium Efficiency Motor Selection And Application Guide: A Guidebook for Industry (energy.gov).

These methods can be used to show the difference between different degrees of alignment for your machines in-plant, resulting in the ability to justify precision alignment through directly measured energy impacts alone, continue the ability of reliability and maintenance to tie to corporate energy and emission goals and improve the bottom line.

Precision Alignment: A Path to Energy Savings and Emission Reductions

And now, back to our alignment case study:

Figure 2: 600 horsepower, 460 Vac, VFD motor and pump.

Total losses of the 600-hp motor were detected as 14%, with a majority (11.1%) related to bearing losses. The approach of correcting to a standard alignment would reduce emissions from 14% to approximately 4% (or by 10%).

Precision alignment can reduce energy losses by up to 12.5%, saving thousands of dollars and tons of CO2 annually.

The shift to a precision alignment would reduce those losses to 1.5% (a reduction of 12.5%). In the end, this represents a reduction of 38.4 Tons of CO2 per year through a standard alignment or a reduction of 48 Tons (or an additional 10 Tons of reduced CO2) through precision alignment.

From an energy-impact standpoint, the losses would be a reduction of 54.3 MWh/year with a standard alignment and 67.9 MWh/year with precision alignment. Considering $0.10/kWh usage, a standard alignment will generate an energy-cost reduction of $5,430, and precision alignment will create a reduction of $6,790. These assumptions, though, don’t consider the self-feeding losses as components fail and the demand charges.

From a reliability standpoint, the energy losses in each area feed the degradation of components. This means that the 11.1 kW losses feeding into the bearing stresses in our 600-hp electric motor translate directly into heat due to friction. The friction is the driver toward failure, degrading lubrication quickly.

Energy losses in misaligned motors feed component degradation, accelerating failure and increasing maintenance costs.

Overall, the impact on energy losses in an electric motor varies exponentially with misalignment. Precision alignment will improve overall reliability and energy costs (immediately measurable), resulting in significantly higher greenhouse gas emissions.

This supports the expectation that a minimum of 14% energy reduction is achievable through the application of a maintenance program. Substantially greater reductions can be accomplished with a precision-maintenance program, which also has the potential to be self-supporting.