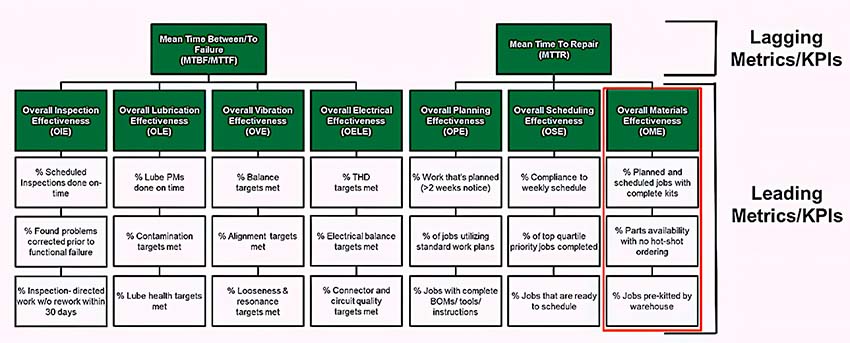

Overall Materials Effectiveness (OSE) is a leading indicator that drives proactive behaviors, which in turn drives asset reliability.

This OME discussion centers on how materials management practices directly impact effective plant maintenance. Metrics that reflect general supply chain and warehouse management practices are important but beyond the scope of leading metrics that drive MTTR performance.

What OME Is and Why It’s Important

Once a maintenance job has been successfully planned and scheduled, it must be successfully executed. Successful execution of maintenance jobs requires the completion of all prework and permitting, a definition of the tools necessary to complete the job, clear work instructions, and the right parts and materials that are required to complete the job staged at the right place at the right time. It should be noted that the parts must also be in the right condition.

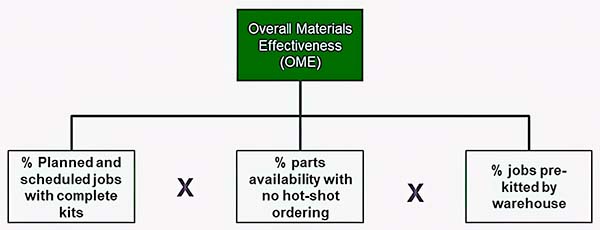

OME is calculated as the product of multiplying the following three input factors:

- Percentage of planned and scheduled jobs with complete kits.

- Percentage of parts availability with no “hot-shot” (expedited) ordering.

- Percentage of jobs pre-kitted by the warehouse.

The simple formula for OME is the product of multiplying the ‘behavioral inventories’ for the three input factors.

When one performs “Day In the Life of” (DILO) studies to determine what prevents crews from efficiently and effectively executing maintenance work, materials unavailability often rises to the top of the hurdles list. In other words, a maintenance job simply cannot or could not be completed with the available parts and materials.

When required parts and materials are unavailable, maintenance craftspeople and their supervisors must either dismiss the job or get busy chasing down the needed items. That often goes as far as phoning suppliers and orchestrating heroic logistics if the maintenance work is deemed critical or important.

In worst-case scenarios, the lack of proper parts and materials forces maintenance crews to make do with substitute parts or scavenge the junkyard of failed machines to extract used components or parts. Both scenarios set the stage for the next failure. But it gets worse.

Maintenance work simply cannot be completed without the right parts and materials.

Consider, for example, if substitute components are used and the organization doesn’t have well-defined bills of materials (BOMs) for its work plans and/or employs a “like for like” parts-exchange methodology for executing repairs. Going forward, the same wrong part could be installed every time the asset requires maintenance, and short component life could become culturally accepted as normal.

As with other leading metrics, we must view the OME elements as an inventory process of binary observations: The job complies or doesn’t. Each element of the OME metric is displayed as a percentage of the complying observations divided by the total number of observations and converted to a percentage.

The OME is the product of multiplying the three components together. If OME increases, we’re practicing behaviors that will drive MTTR down, which is our goal. Let’s explore the three components of OME in more detail.

1. Percent Planned and Scheduled Jobs with Complete Kits

Nothing kills wrench/spanner time performance more than forcing the crews into a parts-chasing mode. As was discussed in the Overall Scheduling Effectiveness (OSE) metric, a job isn’t ready to schedule until the following criteria are met.

- All required parts and materials identified in the bill of material (BOM) must be verified as being on hand.

- Any special tools needed to complete the job, including any outside tools hire, are available.

- Any scaffolding or other required prework has been completed or will be completed before the commencement of job completion.

- Access to the equipment has been approved, permitted, and coordinated with operations as required.

- Job plans and work instructions are complete and wrench/spanner-ready, including the following:

Having all required parts and materials on hand is right at the top of the list of the items necessary to declare a job “ready to schedule.” If the warehouse informs the maintenance scheduler that this requirement has been met when it is, in fact, not the case, the maintenance crew is forced to dismiss the job or go into a reactive mode to find parts.

Nothing kills wrench time more than forcing crews into a parts-chasing mode.

When this happens, the best-case scenario is wasted time. What was to have been a two-person, two-hour job takes all day or gets pushed to another day. In the worst case, the crews have to force-fit parts or scavenge used parts to complete the job, which puts the equipment’s reliability at risk. Having a complete parts kit is imperative to ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of maintenance work execution.

2. Percentage of Parts Availability with No ‘Hot-Shot’ (Expedited) Ordering

Expediting parts to complete a job is expensive. Suppliers often demand a premium to bump other customers and move you to the front of the queue. The cost, however, is just the tip of the iceberg.

The requirement to expedite parts is not only a wrench/spanner time killer, but it can also demand massive amounts of time and effort from supervisors, maintenance managers, engineers, and warehouse personnel. When maintenance jobs frequently require expedited, i.e., hot-shot, parts ordering, it’s an indictment of the entire inspect-to-execute maintenance process.

Expediting parts is not only expensive—it’s a wrench time killer.

Unless a maintenance job is time/distance/cycles-based, wherein assuring parts on hand without hot-shot orders should be a breeze, the maintenance process starts with an inspection. A notification is generated when the inspection reveals that maintenance work is required.

Notifications go through a gate-keeping process, whereby they are denied or approved and, if approved, prioritized. Jobs that are approved and prioritized then enter the planning stage. Once planned, they’re scheduled and executed. Lots can go wrong in that serial process, though.

If the notification isn’t adequately clear, it’s possible that the job won’t be properly approved and prioritized. Or, during the planning process, the job may be incorrectly scoped and not identify the parts and materials required for completion. Or the process of verifying that the necessary parts and materials are on hand before declaring the job “ready to schedule” could fail.

Moreover, the warehouse inventory system might erroneously confirm that the parts are on hand when, in fact, they are not. Any errors in the serial inspect-to-execute maintenance process can produce an expedited-parts-procurement scenario.

Watch your hot-shot-job-percentage performance very closely: It’s a powerful leading metric that reveals flaws in the entire maintenance process. Focusing on behaviors that reduce or eliminate the need for expedited parts orders delivers substantial value to the organization.

3. Percentage of Jobs Pre-kitted by The Warehouse

In an ideal situation, parts and materials will be pre-kitted by the warehouse for easy and convenient pick-up by the maintenance crews. This is a straight-up division of labor to improve efficiency. If a job is properly planned, there’s no reason why it can’t be pre-kitted by the warehouse.

Maintenance crews cooling their heels at a warehouse counter as they wait for a clerk kills wrench/spanner time (and usually captures the ire of plant managers if they see it). Ideally, the parts and materials required to complete jobs are kitted AND staged.

This sensible division of labor makes everyone more productive and allows the organization to complete more high-quality maintenance work with the crew hours for which it is paying.

Pre-kitting and staging materials improves productivity and reduces delays.

Maintenance work can’t be effectively and efficiently executed without the right parts, at the right place, at the right time. Chasing parts is a primary wrench/spanner time performance killer as maintenance crews and their supervisors hunt for whatever is needed to complete a scheduled job.

Resorting to the use of substitute parts that “will fit and do in a pinch” or those scavenged from the junk pile sets the stage for the next failure and compromises reliability.

Take dead aim at Overall Materials Effectiveness (OME) to 1) ensure that you have complete parts and materials kits for scheduled jobs; 2) ensure that jobs requiring hot-shot or expedited parts are minimized; and 3) ensure that your warehouse personnel are pre-kitting and staging materials to improve overall crew productivity.

In short, target leading indicators that drive behaviors to ensure jobs are planned and scheduled properly and materials are managed effectively. Then, watch your operations’ Mean Time to Repair (MTTR) performance drastically improve.

This concludes our seven-part series on proactive leading metrics that drive improved Mean Time Between/To Failure (MTBF/MTTF) and reduced Mean Time to Repair (MTTR). To read previous installments, see the links below. Going forward, I’ll follow up in more detail on several issues raised in these articles and delve into lagging metrics to make clear connections between them and the leading metrics discussed in this series.