Fallor ergo sum. I err; therefore, I am. (St. Augustine)

No one I’ve ever met who operates an automobile repair garage would leave wheel nuts loose because they didn’t feel like tightening them. But many maintenance people get distracted and let a car go out with loose wheel nuts. No surgeon would knowingly leave a sponge, clamp, or anything else in a patient, yet reading the news, it happens all the time.

To err is human; to admit it, superhuman.(Doug Larson)

Everyone makes mistakes. In my classes, I frequently ask if anyone (who has carried tools in their life) has ever caused a worse repair problem while repairing. The only answers to this question are:

- You have.

- You are lying.

Or perhaps you never did anything with the tools you carried. Sorry for being harsh. To make matters worse, the “right” mistakes at the “right” time make us grow and develop in our field. Without errors, growth may very well be impossible.

When anyone touches a machine for any reason, there is a slight chance they will mess something up. What causes this? Another way to ask this question is: What are the causes of error?

Failures of this type, caused by the repair person, are called iatrogenic failures. The word comes from the medical field and is originally from Greek, meaning an illness caused by a doctor or other health professional.

We battle the causes of mistakes while accepting their inevitability. We know the reasons for some mistakes because they are everyday experiences, like fatigue, being preoccupied, or not having enough light.

I remember one job like it was yesterday. I used to have a company that designed, built, installed, and serviced motor fuel management systems. I was called in from Philadelphia to service a system I had installed on Long Island, New York.

It was Friday afternoon, and I knew if I left the job soon, I’d be home in three to four hours, but if I delayed, it might be five or more hours before I got home. Typical for this equipment, I diagnosed it and repaired it in about 45 minutes. So far, so good.

I was installing the metal cover (remember, I was moving quickly), and I didn’t notice that a couple of wires got caught by the lid’s lip. I felt a slight tingle in my hands, the circuit breaker popped, and I smelled the characteristic acrid smell of burned plastic. I removed the cover and saw smoke coming from the circuit boards.

In my haste, I fried all the circuit boards when 220V mains power was routed through the 5V supply and ruined the entire unit. I felt foolish and said things I might not repeat in polite company. That night, I made it home quickly, but I had to return on Monday with a complete set of boards and did the subsequent repair much more carefully!

Create an environment where it’s safe to be honest and start a conversation about mistakes.

The first step is to internalize the learning the mistake shows you. Explicitly ask, “What did I learn from this mistake?” Be ready to share the lesson. Your ability to make a mistake, learn from it, and share it with others makes you a great leader and teacher.

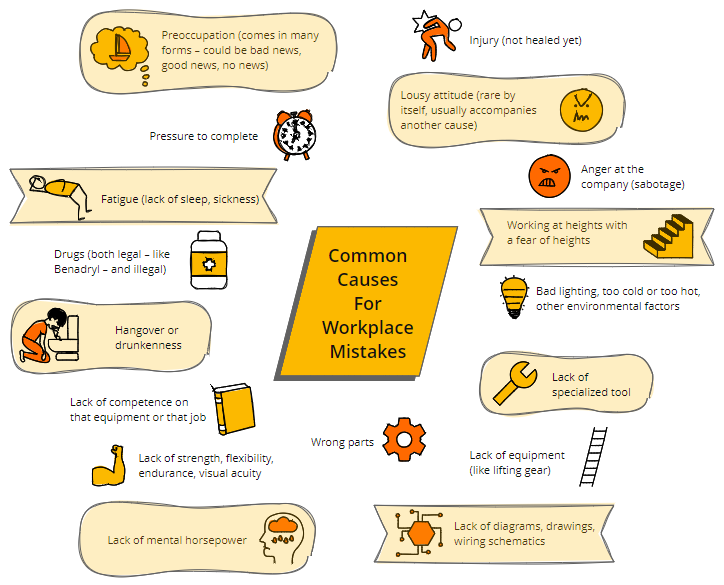

There are many common causes for mistakes we see in the workplace:

The critical question is: How can we manage or eliminate as many of these causes as possible? Presumably, once a cause is eliminated, the chance of a mistake is lowered. The supervisor is in the catbird seat (advantageous perch) to many potential problem areas.

One problem is that we are blanketing our supervisors with computer work, which used to be called paperwork. A best practice is ensuring supervisors spend at least 65% of their time on the floor. If they are on the floor and spending time around the maintenance workers, they can notice some of these issues.

Different people are accountable for various causes of mistakes. Our positions in our companies hold us responsible for specific reasons for errors. For example, workers should report when they are not fit to work, and a boss should be accountable for improving workplace issues like lighting or environmental concerns.

Who Has Primary Accountability?

Workers—Workers are primarily responsible for their work. Pride in a job well done is a strong motivator for people in the maintenance crafts. That pride often forces a second look that catches and fixes many mistakes. If workers cannot do quality work due to a problem listed above, they should complain to their supervisor.

Supervisors – While the workers might be responsible, supervisors are held accountable. They are the ones who should have detected (lack of) fitness to work, bad conditions, excessive hours, and sickness.

Bosses – Bosses should notice and help manage the conditions, keeping the pressure off the workers. Another significant role is to provide unwavering support for good job planning and effective scheduling. Good job planning accounts for the elements of the job being present. That includes parts, PPE, drawings, tools, equipment, and (to some extent) conditions.

How Can We Avoid Mistakes?

Creating a new kind of work environment can help prevent mistakes. Here are a few ideas:

Create an environment where it’s safe to be honest and start a conversation about mistakes.

Create an environment where people can express their shortcomings without ridicule. Creating this culture might be a tall order, but it is essential for everything else. Provide clear guidelines about the mistakes identified above. Can you imagine an environment where people feel OK about sharing their mistakes?

A starting point is ongoing discussions (perhaps as part of toolbox meetings) of past mistakes by the bosses, following this format: “What I did was” and “What I learned was.” Can you see how useful it might be for the young ‘uns to hear the seniors recount what they did wrong and why that made them better tradespeople?

Take a close look and then dig a little deeper.

To learn the causes, study mistakes after they occur, without blaming. Then fix the causes. If you manage the investigation of a mistake, don’t stop at “employee did not follow SOP.” There is always something underneath that cause. A root cause analysis program can help train people to look deeper.

For a program to be successful, it must be driven from the top, with senior leaders making everyone aware of why it’s essential to create a culture that identifies waste and eliminates failure, taking avoiding mistakes to a whole new level.

Finding educational resources on root cause analysis and developing an RCA program is easy. If your organization isn’t already solving problems to the root cause, you have a massive opportunity for improvement.

Look into and support planning efforts.

No one system will reduce mistakes more than effective planning (identifying resources to do a job) and scheduling (making sure the resources get to the job when it starts).

The role of the Maintenance Planner is to improve workforce productivity and work quality by anticipating and eliminating potential delays through planning and coordinating labor, parts and material, and equipment access.

It takes a professionally trained Maintenance Planner to carefully plan and schedule work to maintain the designed reliability of equipment. Job plans created by the Maintenance Planner are intended to ensure or extend equipment life expectancy, reducing maintenance costs and increasing output.

Is your organization using planning and scheduling best practices? If you’re not sure, it is well worth your investment to send at least one Maintenance Planner to training to help them understand best-practice planning and scheduling. And once they are trained, ensure they are supported in bringing about changes within your organization.

Measure mistakes and report on progress.

Figure out how to measure mistakes and report on progress. You might review rework statistics (shows a mistake was made requiring an additional service call) or callbacks (when a maintenance person has to revisit a job that was supposed to be complete) as a starting point. In addition, consider the importance of the messages that are part of your organization’s culture.

If people who fix mistakes after they happen are celebrated as heroes, consider celebrating people who find ways to change situations or processes so that mistakes don’t happen in the first place.

Thanks for reading. Cheers, Joel

Joel Levitt is a renowned trainer in the maintenance industry, having trained over 20,000 professionals from 3,000 organizations across 42+ countries. Since 1980, he has led Springfield Resources, a management consulting firm specializing in maintenance solutions. With 35 years of experience in various maintenance roles, including process control, field service, and maritime operations, Levitt is a frequent speaker at industry conferences and the author of 10 books and numerous articles on maintenance management. He has also served on several boards and committees and is an active member of AFE.